Dogs, Dopamine, and the Data in Every Sniff: What Canines Teach Us About Reward and Human Behavior

I’ve been thinking a lot about why dogs sniff… and sniff again. The more I read, the more I see a clean neuroscience story: sniffing is information-gathering that ties directly into the brain’s reward machinery. And when we compare dogs with humans, we learn something about our own decision-making, habits, even social cues.

DOGSCURIOSITY

Zayera Khan

9/24/20255 min read

Dogs, Dopamine, and the Data in Every Sniff: What Canines Teach Us About Reward and Human Behavior

By Zayera — Curiously connecting animal and human behavior. Questions asked by Zayera & written with ChatGPT.

I’ve been thinking a lot about why dogs sniff… and sniff again. The more I read, the more I see a clean neuroscience story: sniffing is information-gathering that ties directly into the brain’s reward machinery. And when we compare dogs with humans, we learn something about our own decision-making, habits, even social cues.

1) The short science of a long sniff

Dogs are “smell-first” animals. Their noses route odor-rich air efficiently to the olfactory epithelium, and their brains devote substantial circuitry to processing scent. Compared with humans, dogs have far more olfactory receptors, specialized airflow that separates breathing from smelling, and denser “wiring” from the olfactory bulb into networks that handle memory, emotion, and decisions. Reviews that map canine olfaction (and its connections deep into the brain) consistently underscore this architecture advantage.

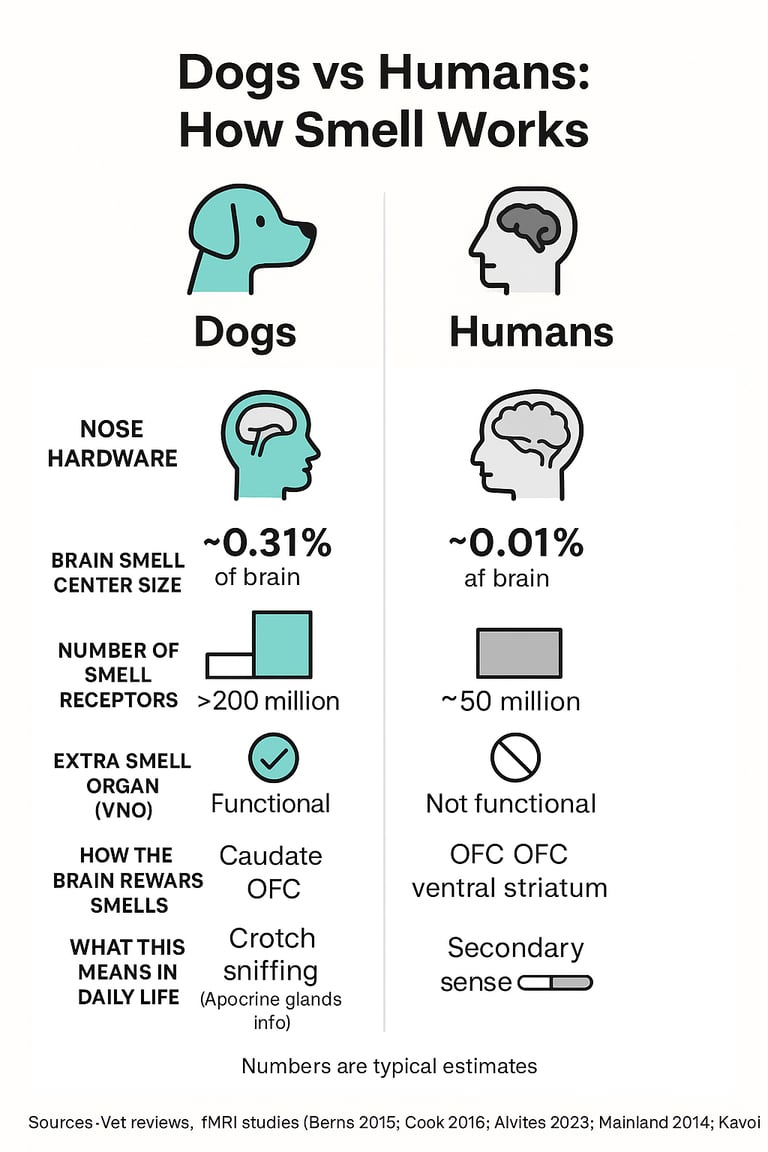

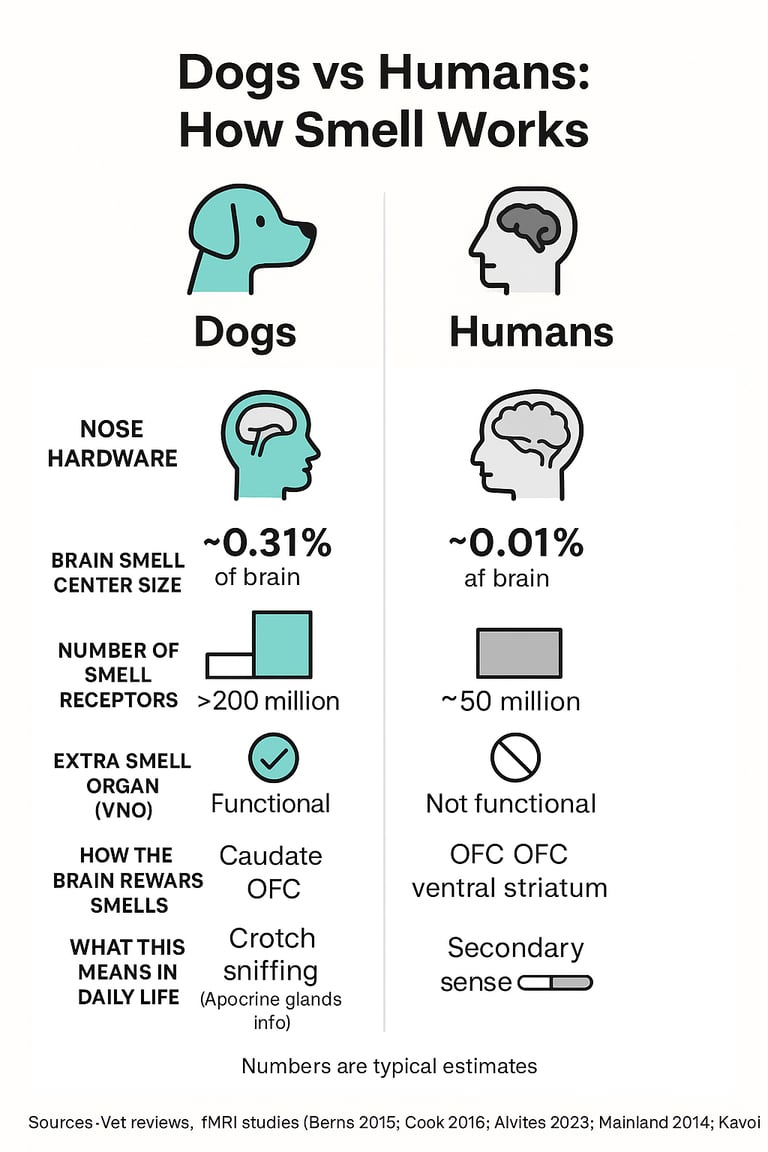

A striking anatomical comparison: the olfactory bulb (the first brain relay for smells) occupies ~0.31% of total brain volume in dogs but ~0.01% in humans—evidence that odour information simply weighs more in canine cognition.

2) Smell → reward: why one good whiff leads to another

In awake, unrestrained dogs (yes, trained to lie still in an MRI), reward centers such as the ventral caudate light up to meaningful scents. The smell of a familiar human (you!) is enough to engage these circuits, and in head-to-head tests many dogs show caudate responses (and real-world choices) that value social praise as much as food. That’s a powerful explanation for repetitive sniffing: when scent predicts something good, dopamine-rich pathways motivate dogs to seek the next rewarding sniff.

The story keeps going downstream: when dogs must separate target odors from distractors, fMRI shows distinct activation patterns for mixtures vs. single odors, suggesting the brain is working hard to decode complex scent scenes—and likely getting rewarded for doing it well.

3) Dogs and humans: what’s the same, what’s different?

Shared circuitry. Both species use homologous reward hubs—ventral striatum/caudate and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC)—to encode the value of pleasant, meaningful stimuli (including smells). In humans, pleasant odors reliably recruit medial OFC and striatal regions; value tracks subjective pleasantness and motivation. Dogs show parallel caudate patterns to socially meaningful scents.

Different inputs. Humans have ~400 functional odorant receptor genes, whereas dogs carry a larger receptor repertoire and many more receptors in the nose. Functionally, dogs detect lower concentrations and extract richer social and environmental information from scent.

Accessory pathway. Dogs possess a functional vomeronasal organ (VNO) that samples social/semiochemical cues; adult humans lack a comparable functional system (no accessory olfactory bulb; evidence for a working VNO in humans is weak). Practically, this means dog social life rides more on smell than ours does.

Net effect. The same reward-learning circuitry exists in both species, but in dogs it’s driven by smell more often and more strongly. In humans, vision and audition typically dominate day-to-day reward learning; odors modulate rather than lead—though pleasant food odors still engage our OFC/striatum and bias choices.

4) The “crotch sniff” decoded (and how to handle it gracefully)

Short answer: it’s social data collection, not rudeness. The groin (and armpits) is packed with apocrine glands that broadcast rich, individual chemical profiles. For a dog, a quick sniff here is like scanning an ID badge—information about sex, hormonal status, stress/arousal, even recent activities—sampled by both the main olfactory system and the VNO. Interest can spike in people who are menstruating, postpartum, or recently sexually active because chemical signals are stronger.

Polite practice: Allow a brief sniff; then cue “all done” and redirect to a sit, hand-target, or permitted “go sniff” elsewhere. You’re leveraging scent as a natural, brain-validated reward while keeping greetings comfortable for humans. (This fits with canine fMRI evidence that social/praise outcomes are rewarding.) (PMC)

5) Sniffing as enrichment—and emotional regulation

Letting dogs “be dogs” with nosework, scent games, and sniff-heavy walks isn’t indulgent; it’s evidence-based welfare. Controlled studies show that nosework can shift dogs toward more optimistic judgment biases (a proxy for positive affect) and calmer behavior—exactly what we’d predict if scent work taps reward systems while satisfying species-typical needs.

Simple ideas to try:

Build “sniff time” into walks (trade distance for quality).

Use sniffing as a reward: release “go sniff” after nice leash manners.

Rotate hide-and-sniff games at home (treats, scented cotton swabs in boxes—avoid irritants).

6) Why this fascinates me (and why it matters to you)

My curiosity sits at the junction of animal behavior, neuroscience, and everyday life. Watching a dog’s nose at work is like watching a live feed into their motivational system—and a mirror for ours. Understanding the smell-to-reward loop helps us:

Train and enrich more humanely (sniffing isn’t “dawdling”; it’s regulatory and rewarding).

Decode mixed signals (a crotch sniff is information-seeking, not misbehavior).

Reflect on humans (our rewards come from different channels, but the brain logic—value, prediction, dopamine—rhymes).

Practical takeaways

Trade distance for data. Shorter walks with dedicated sniff time often produce calmer dogs than long, rushed walks.

Use scent as a reward. After good leash manners or check-ins, release “go sniff.” Your dog’s brain treats this like a treat.

Set greeting rules. Permit a brief crotch sniff, then “all done” → sit/hand-target → reward.

Enrich at home. Scatter-feed, box-puzzles with safe scent cues, or formal nosework classes to tap that sniff–reward loop.

Dogs and humans share the same reward architecture, but dogs feed it far more through smell. When your dog lingers on a patch of grass—or heads straight for a stranger’s apocrine-rich “ID badge”—they’re not being rude or stubborn. They’re running the species-typical program that makes them feel good, calms their system, and keeps their world richly informed. And if we care about behavior (theirs and ours), that’s a loop worth respecting—and using.

References (open-access or authoritative sources)

Berns GS et al. Canine fMRI: familiar human scent engages reward circuitry. Behav Processes (2015). (ScienceDirect)

Cook PF et al. Dogs’ ventral caudate tracks praise vs. food; brain predicts choice. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci (2016). (Oxford Academic)

Prichard A et al. Odor mixtures vs. components in the dog brain (awake fMRI). Chem Senses/J Neurophysiol (2020). (Oxford Academic)

Alvites R et al. Review of companion-animal olfactory bulb anatomy & physiology. (2023). (PMC)

Kavoi & Jameela. Olfactory bulb proportion: dog 0.31% vs human 0.01% of brain volume. Int J Morphol (2011). (scielo.cl)

Mainland JD et al. ~400 functional human OR genes; variability across people. (2013/2015). (PMC)

Meredith M. Human VNO: evidence argues against adult function. Chem Senses (2001). (PubMed)

Jenkins EK et al. >220M receptors in canine nasal cavity (review). Front Vet Sci (2018). (PMC)

PetMD & AKC explain apocrine-rich regions and why dogs sniff the crotch. (2021/2023). (petmd.com)

Duranton C & Horowitz A. Nosework → optimistic bias. Appl Anim Behav Sci (2019) + Barnard PDF discussion (2018). (ScienceDirect)

Human olfactory reward: OFC/striatum track odor pleasantness & wanting. SCAN (2014/2015); NeuroImage (2003). (PMC)

Keywords: dog sniffing behavior, canine olfactory bulb size, dog dopamine reward, ventral caudate dogs, orbitofrontal cortex odor, vomeronasal organ dogs humans, why dogs sniff crotch, nosework benefits, enrichment for dogs#DogBehavior #CanineNeuroscience #Olfaction #Dopamine #Nosework #Sniffari #PositiveReinforcement #DogTraining #AnimalWelfare