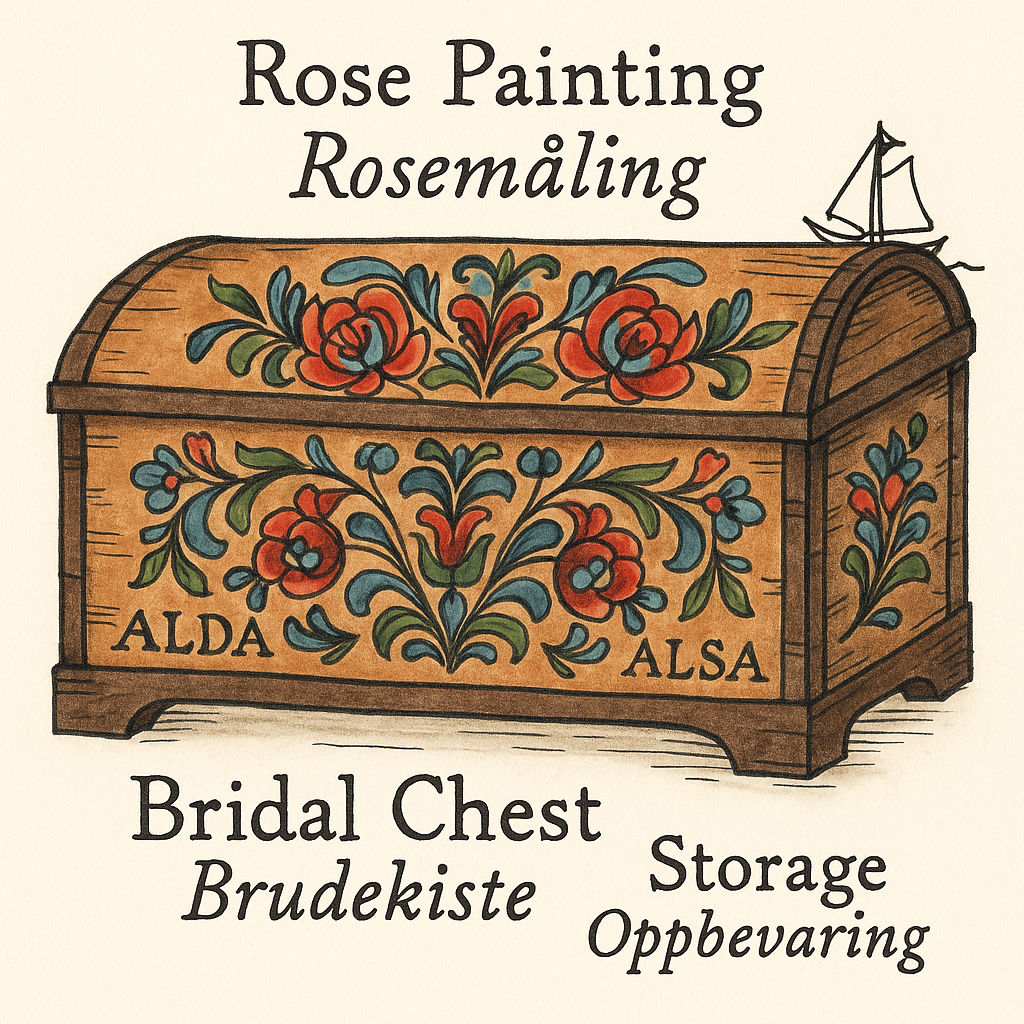

Rose-Painted Chests: More Than Storage, A Piece of Heritage

Rosemaling – the art of rose painting – blossomed in Norway in the mid-18th century and became a defining feature of folk art by around 1850.

NORWAY

Zayera Khan

8/19/20252 min read

Rose-Painted Chests: More Than Storage, A Piece of Heritage

Rosemaling – the art of rose painting – blossomed in Norway in the mid-18th century and became a defining feature of folk art by around 1850. Before its rise, most wooden objects were decorated with pyrography (burned designs, svidekor) or woodcarving (treskurd). The origins of rosemaling can be traced back to church interiors from the 1600s, where Renaissance and Baroque floral garlands adorned ceilings and walls. Over time, this grand decorative language moved into people’s homes, transforming everyday objects into art.

Each rosemaler (painter) developed a personal style, making every piece unique. Since few works were signed, experts today identify artists through subtle details like brushstrokes, flourishes, or the rhythm of floral vines.

By the late 19th century, tastes began to shift. Instead of traditional flowers and scrolls, painters imitated luxury materials like marble, fine wood, or sealskin. One such chest marks the end of the rosemaling tradition on display in the museum.

Most rose-painted chests were produced between 1790 and 1900. They served practical purposes – usually storing clothing – but also held deep symbolic value. Many were bridal chests, filled with the textiles and garments a woman brought into marriage. The initials painted on the front reveal ownership, often with a system like ALDA (Anna Larsdotter Aga) or ALSA (Anders Larsson Aga), where “D” marked dotter (daughter) and “S” stood for son.

For emigrants, these painted chests became heirlooms carried across oceans. Today, the Vesterheim Museum in Iowa preserves one of the largest collections, a testament to how rosemaling traveled with Norwegians and remains a cherished symbol of identity.

Porridge Containers – Everyday Objects with Symbolic Power

Alongside the chests, the museum also displays grautambar – beautifully crafted porridge containers. These were not ordinary kitchen items but ceremonial vessels, holding porridge served at weddings, christenings, haymaking gatherings, and holidays. Whether julegraut (Christmas porridge), barselgraut (postnatal porridge), or bruregraut (bridal porridge), these dishes marked life’s milestones.

At weddings, the serving of bridal porridge was a highlight. Midway through the feast, the toastmaster would strike the table with his borddisk (table disk) and deliver a witty speech about the bride’s supposed efforts in preparing the porridge – a moment of humor that added warmth to the ritual.

The containers themselves were coopered, made from narrow wooden staves bound with hoops. The oldest ones feature pyrographic decorations – geometric fields, stylized sprouts, sun rays, and solar symbols. These motifs were not mere decoration. They carried meanings tied to fertility, growth, and cosmic cycles. The same symbols appear in Hardanger embroidery (svartsaum), on ritual garments, chalk wall drawings (kroting), and even on fiddles.

Later porridge containers were painted in rosemaling, uniting function, beauty, and tradition. Today, they stand as reminders of how everyday objects once carried both practical use and layers of cultural symbolism – vessels not only for food, but also for values, beliefs, and shared celebration.

Image credit: Hand-drawn illustration inspired by traditional Norwegian folk art, created with AI assistance (2025) ChatGPT. Labels in both English and Norwegian for educational use.