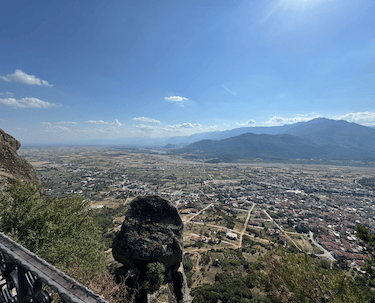

Meteora, Greece the place of monasteries

Plan your Meteora stay: explore Kalambaka and Kastraki, hike cliff-top trails, catch sunset viewpoints, visit unique museums, rock climb (with restrictions), e-bike, and day-trip to alpine villages.

SITES TO VISITTOUR GUIDEGREECE

Zayera Khan

9/14/202514 min read

Meteora at a glance

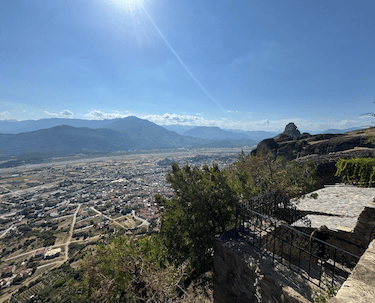

Meteora is a UNESCO World Heritage site in Thessaly: monks settled these near-inaccessible sandstone pillars from the 11th century and built ~24 monasteries; six are active today. See UNESCO’s brief: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/455/

Your base towns:

Kalambaka/Kalampaka – main hub for hotels, cafés, museums, and tours: https://www.kalampaka.com/en/ and the DMO: https://www.infotouristmeteora.gr

Kastraki – quieter village under the rocks, perfect for walkers/photographers: https://visitmeteora.travel/kastraki-village-meteora

Short history—how a sky city took shape

Hermits first occupied caves/ledges; organized monastic life took off in the 14th–15th c. Under St Athanasios the Meteorite, the Great Meteoron became the model house; 24 monasteries rose in total. UNESCO overview: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/455

For centuries access was by ladders and rope nets; staircases were later additions as communities stabilized. (UNESCO background & site histories at https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/455

The six living monasteries you can visit

Four are male communities, two are female (nunneries):

Monks: Great Meteoron, Varlaam, Holy Trinity (Agia Triada), St Nicholas Anapafsas.

Nuns: Rousanou/St Barbara, St Stephen (Agios Stefanos).

Visit Meteora monasteries page: https://visitmeteora.travel/meteora-monasteries/

Rousanou convent (became a nunnery in 1988): https://visitmeteora.travel/monastery-of-roussanou-visit-meteora/

St Stephen (converted to a nunnery in 1961): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monastery_of_Saint_Stephen_(Meteora)

Why are some monasteries male and others female?

Eastern Orthodox monastic life is gender-segregated by tradition. Women aren’t ordained to the priesthood, so convents rely on visiting clergy for sacraments while the abbess leads the community’s life. See the Orthodox Church in America’s Q&A: https://www.oca.org/questions/priesthoodmonasticism/ordination-of-women .

For context on gendered sacred space, compare Mount Athos’ avaton (women prohibited) with Meteora’s open access: overview at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monastic_community_of_Mount_Athos and an explainer on the avaton rule: https://athos.guide/en/blog/avaton-en . (Meteora does not ban women.)

A feminist read—space, access, and women’s agency

Access with boundaries: Meteora welcomes women visitors (unlike Athos) but keeps dress codes—long skirts for women, covered shoulders, long trousers for men. Local etiquette: https://visitmeteora.travel/meteora-monasteries-visiting-etiquette/

Women as restorers & hosts: After wartime damage/decline, St Stephen revived as a convent (1961); Rousanou followed (1988), placing women at the center of preservation and daily hospitality. Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monastery_of_Saint_Stephen_and https://visitmeteora.travel/monastery-of-roussanou-visit-meteora/

Everyday leadership: Reporting from St Stephen notes ~30 sisters in recent years—a visible female monastic presence negotiating prayer, tourism, and heritage. Example feature: https://www.globalsistersreport.org/monasteries-sky-life-seclusion-meets-tourism

Living heritage lens: Scholars frame Meteora as a living heritage site balancing devotion, conservation and tourism. Free book (UCL): https://www.ubiquitypress.com/books/19/files/ac911695-3723-4d6f-a4c0-5efa85041496.pdf

What to do in the Meteora region

1) Hike between rocks and chapels

Trail maps: volunteer project with GPS tracks: https://meteoratrails.com/

Classic viewpoints: Psaropetra / “Sunset Rock” near Rousanou—great at golden hour. See a locator write-up: https://www.lonelyplanet.com/greece/meteora/attractions/psaropetra-lookout/a/poi-sig/1383529/1316628

Official area map: download from the local DMO: https://www.visitmeteora.travel/our-map-of-meteora/ (free sign-up).

2) Visit museums & rainy-day gems (in Kalambaka)

Natural History & Mushroom Museum (+ truffle-hunting experiences): https://meteoramuseum.gr/plan-your-visit-to-museum and https://meteoramuseum.gr/truffle-hunting

Hellenic Culture Museum (rare books/education heritage): https://www.bookmuseum.gr/en/visit/ .

Digital Projection Centre (short 3D history show): municipal page https://www.infotouristmeteora.gr/main-menu/sights/museums/digital-projection-centre-of-meteoras-history-and-culture/

3) Theopetra Cave—now reopened

Prehistoric cave (evidence of continuous presence for ~130,000 years) a few km from town; reopened in April 2025. Hours often listed as 08:30–15:30, closed Tue—check locally.

Ministry page: https://odysseus.culture.gr/h/2/eh251.jsp?obj_id=1616

Reopening news: https://greekreporter.com/2025/04/15/greece-theopetra-cave-reopens-after-9-years/

Local practicals: https://visitmeteora.travel/prehistoric-cave-of-theopetra/

(Also see the Documentation & Education Center listing: https://archaeologicalmuseums.gr/en/museum/5df34af3deca5e2d79e8c16a

4) Explore by e-bike (low-impact, fun)

Local operator info & rentals: https://meteoraebike.com/ and sample tour: https://visitmeteora.travel/tour/meteora-sunset-e-bike-tour/

5) Rock climbing—know the rules

Meteora is historic for climbing, but climbing is forbidden on rocks with active monasteries/chapels/visible ruins. Read the local Code of Ethics: https://visitmeteora.travel/meteora-code-of-ethics/ . (Other sectors exist—go with local guides.

6) Easy photo loops & short walks

Drive or bus the upper road and stop at signed lay-bys for views of Rousanou, Varlaam, and Great Meteoron; combine with short stair climbs to one or two interiors. (Use the map above and viewpoint refs: Psaropetra page.)

7) Day trips from Meteora

Elati & Pertouli (≈1 hr): alpine villages; winter Pertouli Ski Center: https://www.elameteoratrikala.com/en/elati-pertouli/see-and-do/pertouli-ski-center and local guide https://www.pertouli.net/en/

Trikala city (30–40 min): at Christmas the Mill of the Elves becomes Greece’s biggest festive park (seasonal): background example https://greece.redblueguide.com/en/the-mill-of-elves-in-trikala-an-amazing-christmas-park-full-of-surprises-4

Practical notes

Dress code to enter monasteries: women—long skirts & covered shoulders; men—long trousers; no sleeveless tops. Details: https://visitmeteora.travel/meteora-monasteries-visiting-etiquette/

Hours/closures: each monastery has its own timetable and weekly closure—confirm locally or via the area map: https://www.visitmeteora.travel/our-map-of-meteora/

Respect the site: this is a living monastic landscape—follow signs, keep voices low, and use marked trails. Code of Ethics: https://visitmeteora.travel/meteora-code-of-ethics/

Resources

UNESCO Meteora: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/455/

Municipal info & museums: https://www.infotouristmeteora.gr/

Visit Meteora (DMO—maps, etiquette, tours): https://visitmeteora.travel/

Monastery profiles: Rousanou https://visitmeteora.travel/monastery-of-roussanou-visit-meteora/ ; St Stephen https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monastery_of_Saint_Stephen_(Meteora)

Living heritage scholarship (free PDF): https://www.ubiquitypress.com/books/19/files/ac911695-3723-4d6f-a4c0-5efa85041496.pdf

Theopetra Cave (official & reopening): https://odysseus.culture.gr/h/2/eh251.jsp?obj_id=1616 ; https://greekreporter.com/2025/04/15/greece-theopetra-cave-reopens-after-9-years/ ; local practicals https://visitmeteora.travel/prehistoric-cave-of-theopetra/ .

Hiking map: https://meteoratrails.com/

E-bike ideas: https://meteoraebike.com/ ; https://visitmeteora.travel/tour/meteora-sunset-e-bike-tour/ .

Rock-climbing rules: https://visitmeteora.travel/meteora-code-of-ethics/ . (Visit Meteora)

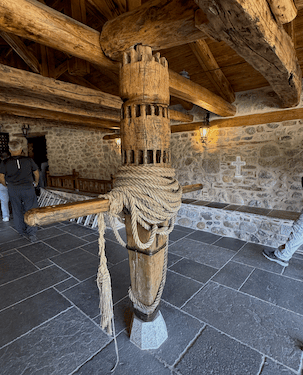

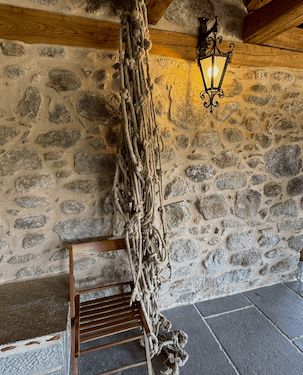

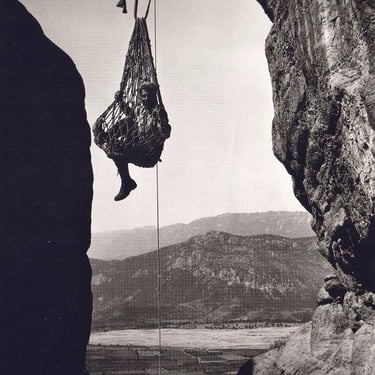

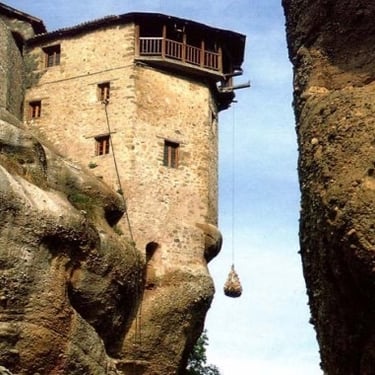

How the monks “towed” themselves up to Varlaam Monastery

High above Kastraki, the Holy Monastery of Varlaam once relied on rope ladders and a net hoist to reach its eyrie. UNESCO even highlights the scene: “the net in which intrepid pilgrims were hoisted up vertically alongside the 373-meter cliff where Varlaam dominates the valley”—a symbol of a way of life now fading. Read UNESCO’s listing: whc.unesco.org/en/list/455

How it worked

A basket/net was attached to a windlass (pulley + winch) mounted in the tower. Monks—and sometimes pilgrims—were hauled up along the cliff face; goods came the same way. You can still see the preserved pulley tower and net at Varlaam today (look for it by the museum rooms): visitmeteora.travel/the-monastery-of-varlaam-meteora.

From nets to steps

Early access was by long ladders and the rope net; stone steps carved into the rock and a small bridge followed in the 19th century. Today, the hoist remains—but is used for cargo and powered electrically, while visitors use the stairs. Source: kalampaka.com/en/meteora-monasteries/monastery-of-varlaam

The famous “replace the rope” line

Travel lore says the ropes were replaced only “when the Lord let them break.” Treat it as legend that captures the monks’ faith and risk, not a maintenance plan. Background: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meteora

Holy Monastery of Saint George “Mandila,” Meteora — The Cliff of Scarves

Tucked into a natural cave on Holy Spirit Rock (Agio Pnevma) above Kastraki, the Holy Monastery of Saint George “Mandila” is a small hermitage you admire from below—access is for experienced climbers only. Every year on April 23 (Feast of St. George), locals climb up to hang scarves (mandilia) as vows and prayers, creating the vivid “cliff of scarves” you can spot opposite Panagia Doupiani.

Learn more on the official pages: Monastery of Saint George Mandila and the ritual overview, “Hanging of mandilins”.

Quick visit tips

Best viewing: paths and lanes around Panagia Doupiani at Kastraki’s edge; look up to spot the scarf-lined cave. Visitor guidance: Visit Meteora

Timing: late April around St. George’s Day; it’s a local, live tradition, not a show.

Context: the site sits within the Meteora–Pyli UNESCO Global Geopark—read the UNESCO profile here.

Please don’t attempt the climb yourself; enjoy the view from marked paths and respect the ongoing religious custom. Local notes: InfoTourist Meteora. (infotouristmeteora.gr)

Varlaam Monastery, Meteora — Library, Learning, and Monastic Life

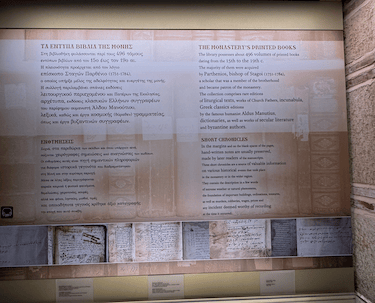

The Monastery’s Printed Books

The library holds about 496 volumes of printed books dating from the 15th to the 19th century. Most were acquired by Parthenios, bishop of Stagoi (1751–1784)—a scholar, member of the brotherhood, and later patron of the monastery.

The collection includes:

Rare editions of liturgical texts and Church Fathers.

Incunabula and Greek classics, including editions by Aldus Manutius.

Dictionaries and secular literature, along with works by Byzantine authors.

“Short Chronicles” in the Margins

On many volumes, handwritten notes by later readers survive in the margins and blank spaces. These brief jottings are valuable sources for the history of the monastery and the wider region, recording in a few words:

Extreme weather and natural phenomena,

Foundations of buildings, ordinations and tonsures,

Murders, robberies, wages, prices—any incident deemed worth recording at the time.

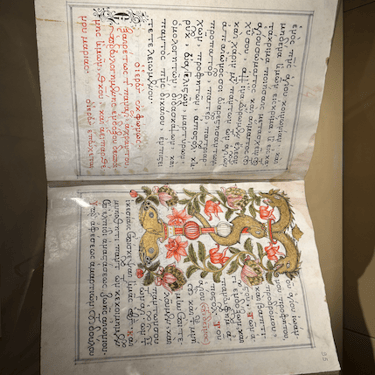

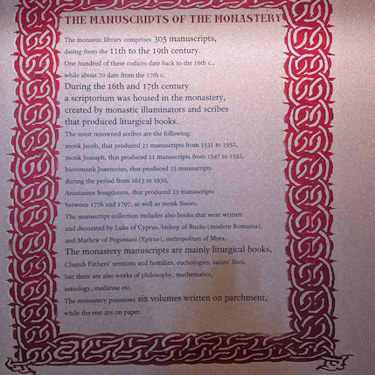

The Manuscripts of the Monastery

Varlaam’s monastic library comprises 305 manuscripts (11th–19th c.). About 100 date to the 16th century and ~70 to the 17th century.

During the 16th–17th centuries the monastery maintained a scriptorium where monastic illuminators and scribes produced liturgical codices.

Noted scribes include:

Monk Jacob — 21 manuscripts (1531–1552)

Monk Joasaph — 21 manuscripts (1547–1552)

Hieromonk Joannicius — 15 manuscripts (1613–1630)

Anastasios Sougdouris — 23 manuscripts (1776–1797)

Monk Sisoes — active copyist

The collection also preserves books written and ornamented by Luke of Cyprus, bishop of Buzău (modern Romania), and Mathew of Pogoniani (Epirus), metropolitan of Myra.

Most manuscripts are liturgical—sermons and homilies of the Fathers, euchologia, and lives of saints—but there are also works in philosophy, mathematics, astrology, and medicine.

Six volumes are written on parchment; the rest on paper.

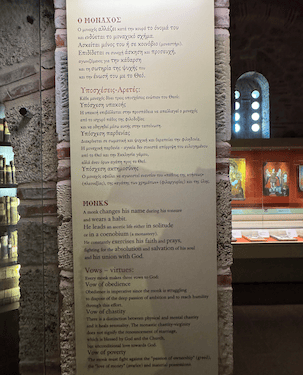

Monks: Vocation and Vows

At tonsure a monk changes his name and puts on the habit. He pursues an ascetic life either in solitude or within a coenobium (monastery), exercising faith and prayer for the absolution and salvation of the soul and union with God.

Three vows—virtues:

Obedience — the struggle against ambition and the path to humility.

Chastity — both physical and mental; not a denial of the sacrament of marriage (which is blessed by God and the Church), but unconditional love toward God.

Poverty — warfare against the “passion of ownership,” avarice, and material attachments.

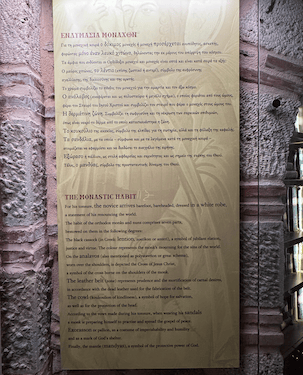

The Monastic Habit (seven parts)

For tonsure the novice comes barefoot and bareheaded, wearing a white robe to signify renunciation of the world. The full habit consists of:

Black cassock (lention / zostikon / anteri) — joy in God, justice, and virtue; its colour also signifies mourning for the sins of the world.

Analavos (polystavrion or great schema) — worn over the shoulders, bearing the Cross of Jesus Christ.

Leather belt (zone) — prudence and the mortification of carnal desires.

Cowl (koukoulion) — hope of salvation and protection of the head.

Sandals — readiness to practise and spread the gospel of peace.

Exorasson / pallion — a cloak of imperishability and humility; a sign of God’s shelter.

Mantle (mandyas) — symbol of the protective power of God.

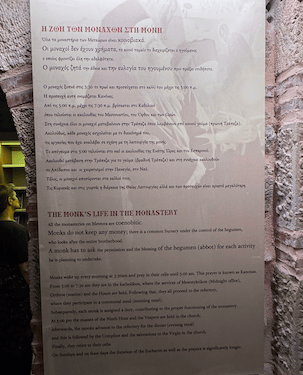

Daily Life in the Coenobium

All Meteora monasteries are coenobitic. Monks keep no personal money; a common bursary under the hegumen (abbot) supports the brotherhood. For any task the monk seeks the hegumen’s blessing.

Schedule (ordinary days):

03:30–05:00 — Prayer in cells (kanonas).

05:00–07:30 — In the katholikon for Midnight Office (Mesonyktikon), Orthros (Matins), and the Hours.

Morning — Common meal in the refectory; then each monk performs his assigned duty for the good order of the monastery.

17:00 — Ninth Hour and Vespers in church.

Evening — Common dinner, followed by Compline and Salutations to the Virgin; then rest in cells.

Sundays & feasts — the Eucharist and prayers are longer.

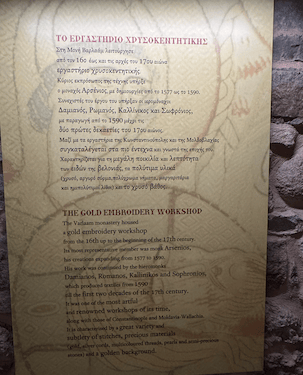

The Gold-Embroidery Workshop

Varlaam housed a renowned gold-embroidery workshop from the 16th to the early 17th century.

Leading master: Monk Arsenios (works dated 1577–1590).

Continued by hieromonks Damianos, Romanos, Kallinikos, and Sophronios (from 1590 to the first decades of the 17th c.).

Alongside the ateliers of Constantinople and Moldavia–Wallachia, Varlaam’s workshop was among the most accomplished of its time, noted for:

Great variety and delicacy of stitches,

Use of precious materials (gold and silver cords, multicoloured threads, pearls, semi-precious stones),

Characteristic golden ground.

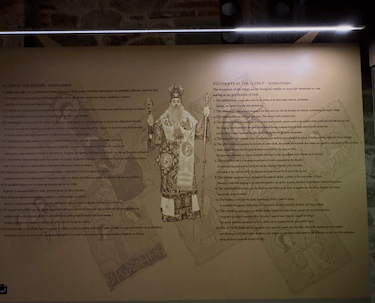

Vestments of the Clergy — Symbolisms (overview)

The panel explains the symbolism of episcopal and priestly vestments, understood as glorifying God:

Sticharion (white tunic): purity and spiritual joy.

Orarion (deacon’s stole): borne on the left shoulder, sign of angelic service.

Epimanikia (cuffs): God’s creative hand and the binding of the wrists to His work.

Epitrachelion (priest’s stole): grace of the priesthood, the yoke of Christ.

Zone (belt): strength, readiness, and chastity.

Phelonion (chasuble): garment of righteousness, overshadowing of the Spirit.

Epigonation / Palitza (diamond-shaped panel): spiritual sword and reward for service.

Sakkos (bishop’s tunic): humility and service, heir to imperial ceremonial attire.

Omophorion (bishop’s pallium): Good Shepherd carrying the lost sheep—pastoral care.

Mitre (crown): kingship of Christ and victory.

Pastoral staff: authority to guide and protect.

Pectoral icons (engolpia): medallions of Christ and the Theotokos, witness to the Incarnation and reminder of episcopal duty.

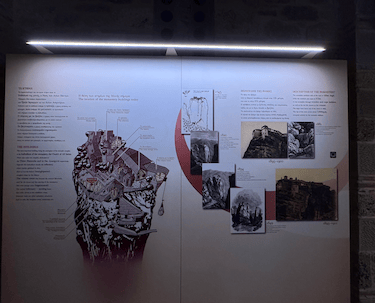

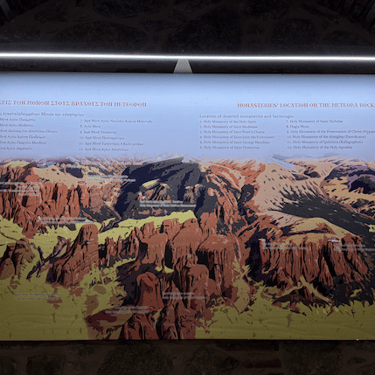

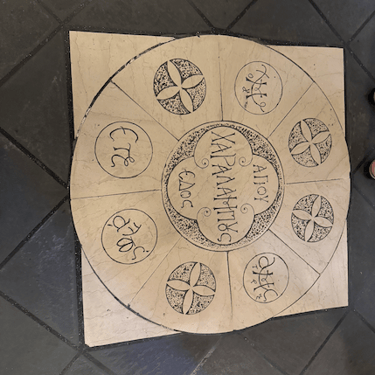

Monasteries on the Meteora Rocks

A panoramic panel maps both active and deserted foundations, including: Holy Spirit, Saint Modestos, Saint Peter’s Chains, Saint John the Forerunner, Saint George Mandilas, Saint Demetrios, Saint Nicholas, Hagia Moni, Ypapanti (Presentation of Christ), Pantokrator (the Almighty), Kalligraphon / Postelnik, and the Holy Apostles. A “You are here” mark situates Varlaam among the rock pinnacles.

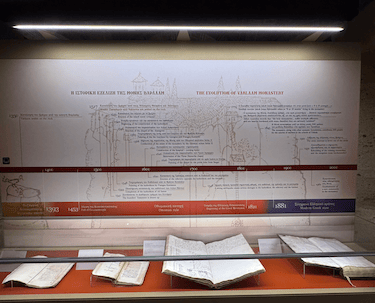

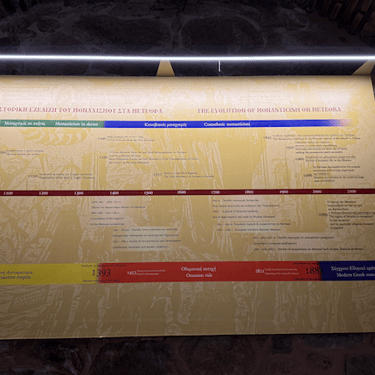

The Evolution of Monasticism at Meteora (timeline highlights)

From 11th-century hermits and early sketes (e.g., Doupiani) to the coenobitic communities of the 14th–16th centuries (including the founding and 1517 revival of Varlaam), the timeline traces phases of construction, intellectual and artistic flourishing, later decline and renewal, and the 1988 inscription of Meteora as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Varlaam Monastery, Meteora — A concise, source-based overview

All information below is transcribed and lightly edited for clarity from on-site museum panels at the Holy Monastery of Varlaam, Meteora (photos in this post). Headings follow the structure of the exhibits: “Hospital–Nursing Home,” “The Evolution of Varlaam Monastery,” “The Founders,” “The Location of the Monastery Buildings Today,” and “Portable Icons.”

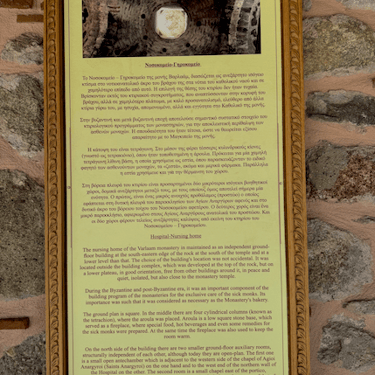

Hospital – Nursing Home (Nosokomeio–Girokomeio)

The monastery maintained an independent, ground-floor Hospital/Nursing House on the south-eastern edge of the rock, to the south of the katholikon (main church) and on a slightly lower level. Its position was deliberate: outside the dense building core, on a quiet, well-oriented plateau—peaceful, isolated, yet close to the monastery temple.

During the Byzantine and post-Byzantine periods, such a facility was a standard and necessary component of monastic building programs, serving the exclusive care of sick monks—regarded as essential as the monastery bakery.

The ground plan is square. At the center stand four cylindrical piers (the tetrakion) that carried the roof; between them lay the aroula, a low square stone hearth. This hearth functioned as a fireplace for preparing special foods, hot beverages, and remedies, and also heated the room.

On the north side are two small, ground-floor auxiliary rooms, open plan yet structurally independent. One forms a modest antechamber adjoining the west side of the Chapel of the Holy Unmercenaries (Agioi Anargyroi). The other is a small chapel dedicated to the same saints. Each room has its own independent roof, separate from that of the main Hospital/Nursing House.

The evolution of Varlaam Monastery — key milestones

c. 1350 — The hermit Varlaam ascends the rock (c. 373 m high), establishes a few cells and two small chapels.

After Varlaam’s death — The rock lies uninhabited for a period.

1517 — Revival by the brothers Theophanis and Nektarios (Apsaras) from Ioannina.

Early–mid 16th century — Major building campaign: erection of the katholikon (Church of All Saints), renewal/continuation of the earlier chapel tradition (Three Hierarchs), and development of functional buildings (refectory, kitchen, hospital, water storage, workshops).

18th–19th centuries — Repairs, restorations, and adaptations recorded on the site plans and images.

Modern era — Integration into the modern Greek state and continued conservation.

The founders: Theophanis and Nektarios (Apsaras)

The two founders descended from an old Byzantine family (Apsaras). Their parents—together with three sisters—lived ascetically on nearby rocks. The brothers embraced monastic life and, after periods of ascetic practice, revived the deserted rock of Varlaam in 1517.

They organized the major 16th-century construction program: they raised the katholikon dedicated to All Saints, maintained the church of the Three Hierarchs (linked to the earlier hermit tradition), and equipped the monastery with essential service buildings (refectory, kitchen, hospital, cistern/well). According to the panels, Saint Theophanis died in 1544 and Saint Nektarios in 1550.

Monk Varlaam (the first inhabitant)

The first known inhabitant was the hermit Varlaam, who climbed the rock around 1350. After his repose the site remained uninhabited until the Apsaras brothers revived it in the 16th century.

The location of the monastery buildings today

A site diagram on the panel identifies the principal structures arranged atop the pillar of rock:

Katholikon (Church of All Saints) — the principal church.

Church of the Three Hierarchs — the smaller, older chapel.

Refectory (Trapeza) — today used as the museum.

Kitchen and bakery, Hospital/Nursing House, cistern(s), workshops and storerooms, cells, and abbot’s quarters.

Windlass/net tower — recalling the historic system of ladders, ropes, and nets used to lift people and supplies before the modern stairway.

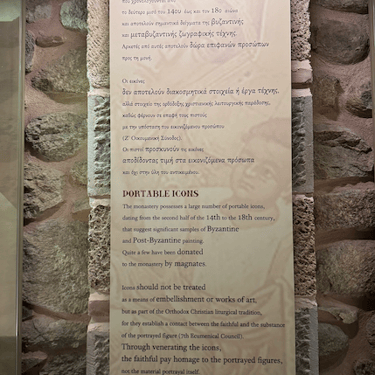

Portable icons

Varlaam preserves a large number of portable icons dating from the late 14th to the 18th century, representing significant examples of Byzantine and Post-Byzantine painting. Many were donated by magnates.

The panels stress that icons are not merely decorative art. In Orthodox Christian liturgy they establish a contact between the faithful and the hypostasis (person) portrayed (as affirmed by the 7th Ecumenical Council). Veneration is offered to the depicted figures, not to the material object itself.

Sources (on-site)

“Hospital–Nursing Home” panel (bilingual GR/EN).

“The Evolution of Varlaam Monastery” timeline (bilingual GR/EN).

“The Founders of the Monastery: Theophanis and Nektarios” & “Monk Varlaam” panels (bilingual GR/EN).

“The Location of the Monastery Buildings Today” (site plan).

“Portable Icons” (theological note on icons).

Photos: museum panels at the Holy Monastery of Varlaam, Meteora.

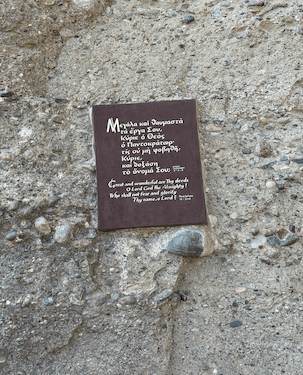

St Stephen’s Monastery, Meteora — history, theology of images, and the monastic center

Transcribed and lightly edited for clarity from the English-language museum panels you photographed at Meteora. Section headings follow the original boards: “St. Stephen’s Monastery,” “The Orthodox Byzantine Painting,” and “The Monastic Center of the Holy Meteora.” Sources listed at the end.

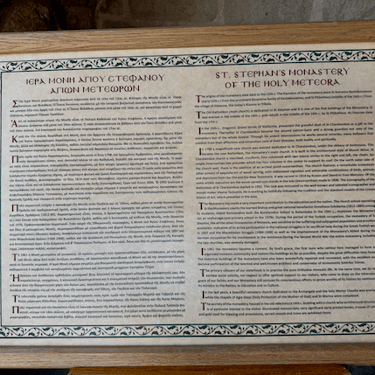

St. Stephen’s Monastery of the Holy Meteora

Origins & founders. The monastery’s history reaches back to the 12th century. Its founders are recorded as St Antonios Kantakouzinos (early 15th c.), from the Byzantine Kantakouzenos family, and St Philotheos (mid-16th c.) from the village of Stagoi (present-day Trikala).

Old katholikon. The former main church, dedicated to St Stephen, was among the first buildings on the rock. It was erected mid-14th c. and rebuilt mid-16th c. by St Philotheos. The interior frescoes date to the 18th century.

Relic of St Charalambos. In the 18th century, Grand Voevod Dragomir of Wallachia offered the monastery the skull of St Charalambos. From then on St Charalambos became the monastery’s second patron and a powerful protector widely venerated across Greece; countless believers sought relief from bodily and spiritual afflictions through his intercessions.

New katholikon (1798). Under Abbot Ambrosios a magnificent new church was dedicated to St Charalambos in 1798; it became the monastery’s katholikon, while the older church functioned as a chapel. The carved wooden iconostasis (screen) was executed in 1814 by Kallistos and Demetrios from Metsovo. The iconographic program follows post-Byzantine tradition, drawing on the Cretan School and Athonite standards; later additions harmonize with these models.

Benefactors & trials. In the 19th century the learned bishop and national benefactor Dorotheos Scholarios (1832–1880) supported extensive renovations and works for the monastery and for education. In the Second World War the monastery suffered bombardment; buildings were damaged and left roofless for a time before restoration.

A women’s monastery (from 1961). In 1961 St Stephen’s became a convent. The first sisters re-established the community, undertook restoration, and developed charitable and pastoral work for the local society and beyond.

Recent additions & treasures. In recent decades a new katholikon has been erected, dedicated to the Archangels and the Holy Martyr Claudia. The monastery preserves precious relics (including the skull of St Charalambos and fragments of the True Cross), hierarchs’ vestments, manuscripts, early printed books, crosses, silver and liturgical vessels, as well as icons used in blessings and processions.

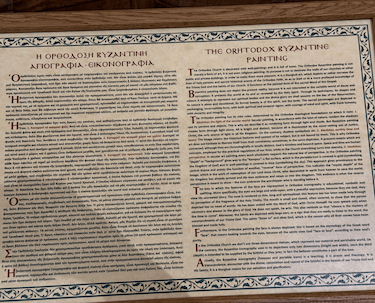

The Orthodox Byzantine Painting (iconography)

The panel explains that Orthodox church decoration consists of wall-paintings and icons. This is not mere embellishment or secular art; it is liturgical art that narrates sacred history and deepens knowledge of the Faith, ultimately guiding the worshipper from the letter of the Gospel to its spirit.

Key theological-aesthetic principles highlighted:

Symbolic, not naturalistic. Iconography does not depict the decaying material world; it renders the transfigured reality sanctified by the Holy Spirit.

Spiritual light. Figures are filled with inner light; shadows are minimized or eliminated.

Abolition of purely earthly constraints. Icons annul ordinary space and time: saints belong to God’s eternity; compositions avoid anecdotal realism.

Reverse/intentional perspective. Perspective serves theology, drawing the viewer into the scene (“reverse perspective”), rather than constructing a vanishing point within it.

Frontal presence. Faces are typically shown frontally so the saints meet us “face to face,” inviting a personal relationship rather than theatrical distance.

Didactic purpose. Frescoes and portable icons function as teaching: a “written theology in colour.” Their aim is the consolation and hope of the faithful and the glorification of the Holy Trinity and His saints.

Two-dimensional discipline. The Church does not employ three-dimensional statuary within liturgical space; iconography works primarily in two dimensions (height and width), using depth only as theology requires.

Orthodox ascetic ethos. Colour, line and composition serve spiritual clarity, moral courage and truthfulness, not spectacle.

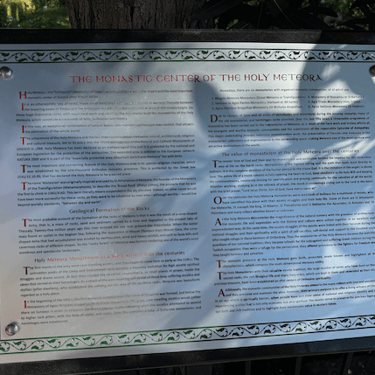

The Monastic Center of the Holy Meteora

Significance. The Holy Meteora—the “stone city” above Stagoi/Trikala—is the largest and most important monastic center in Greece after Mount Athos. It was inscribed by UNESCO (1988) and is part of NATURA 2000; the site combines outstanding cultural and natural value.

Name & founders. The term “Meteora” (“suspended in air”) is attributed to St Athanasios of Meteora, founder of the Great Meteoron (Transfiguration), who established the first organized coenobium on the rocks in the 14th century.

Geology (in brief). The rocks likely formed from ancient conglomerate deposits laid down by watercourses in a prehistoric basin. Subsequent tectonic uplift and erosion sculpted the towers we see today—sheer pillars perfectly suited for the eremitic and monastic ideals of withdrawal and watchfulness.

Evolution of Meteora monasticism. Early hermits and small sketes settled the rocks; later, organized coenobitic monasteries flourished, building churches, refectories, cisterns and workshops. Across centuries of turmoil, restoration and spiritual renewal continued.

Six active monasteries today (organized communities under abbots/abbesses):

Great Meteoron (Transfiguration),

Varlaam,

Rousanou / St Barbara,

St Nicholas Anapafsas,

Holy Trinity,

St Stephen.

Enduring value. Meteora’s monastic witness testifies to love of God, ascetic striving, and service to the Church and the nation through prayer, education, copying of books, charitable works and the preservation of an incomparable spiritual-cultural landscape.

Sources (on-site)

“St. Stephen’s Monastery of the Holy Meteora.”

“The Orthodox Byzantine Painting.”

“The Monastic Center of the Holy Meteora.”

(All texts above are faithful transcriptions, lightly edited for readability, from the English panels displayed at Meteora using ChatGPT September 2025)